It is possible to play Go with a simple paper board and coins or plastic tokens for the stones. More popular midrange equipment includes cardstock, a laminated particle board, or wood boards with stones of plastic or glass. More expensive traditional materials are still used by many players.

Traditional equipmentBoards

The Go board - generally referred to by its Japanese name goban - typically measures between 45 cm (17.7 in) and 48 cm (18.9 in) in length (from one player's side to the other) and 42 cm (16.5 in) to 44 cm (17.3 in) in width. Chinese boards are slightly larger, as a traditional Chinese Go stone is slightly larger to match. The board is not square; there is a 15:14 ratio in length to width, because with a perfectly square board, from the player's viewing angle the perspective creates a foreshortening of the board. The added length compensates for this.[36] There are two main types of boards: a table board similar in most respects to other game boards like that used for chess, and a floor board, which is its own free-standing table and at which the players sit.

The traditional Japanese goban is between 10 cm (3.9 in) and 18 cm (7.1 in) thick and has legs; it sits on the floor (see picture to right), as do the players.[36] It is preferably made from the rare golden-tinged Kaya tree (Torreya nucifera), with the very best made from Kaya trees up to 700 years old. More recently, the related California Torreya (Torreya californica) has been prized for its light color and pale rings, as well as its less expensive and more readily available stock. The natural resources of Japan have been unable to keep up with the enormous demand for the slow-growing Kaya trees; both T. nucifera and T. californica must be of sufficient age (many hundreds of years) to grow to the necessary size, and they are now extremely rare at the age and quality required, raising the price of such equipment tremendously.[37] In Japan, harvesting of live Kaya trees is banned, as the species is protected; the tree must die of natural causes before it is harvested. Thus, an old-growth, floor-standing Kaya goban can easily cost in excess of US$10,000 with the highest-quality examples costing more than $60,000.[38]

Other, less expensive woods often used to make quality table boards in both Chinese and Japanese dimensions include Hiba (Thujopsis dolabrata), Katsura (Cercidiphyllum japonicum), Kauri (Agathis), and Shin Kaya (various varieties of spruce, commonly from Alaska, Siberia and China's Yunnan Province).[37] So-called Shin Kaya is a potentially confusing merchant's term: shin means "new", and thus shin kaya is best translated "faux kaya"—the woods so described are biologically unrelated to Kaya.[37] Beginning in the early 2000s, some boards have been made by compositing strips of bamboo to create a material called "bamboo plywood" or "plybamboo". The resulting board is very durable and has a unique aesthetic, while being relatively inexpensive.

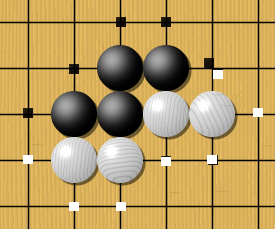

StonesA full set of Go stones (goishi) usually contains 181 black stones and 180 white ones; a 19×19 grid has 361 points, so there are enough stones to cover the board, and Black gets the extra odd stone because that player goes first. There are two main types of stones: single-convex, in which one side is flat, and double-convex, in which both sides have a similar curve. Each type has its pros and cons: single-convex stones, placed flat side down, are less prone to move out of position if the board is bumped or disturbed by nearby movement. In addition, during post-game analysis, players can try out variations using upside-down stones, making it easy to remember the actual game moves. On the other hand, flat stones are harder to clear from the board at the end of the game.

Traditional Japanese stones are double-convex, and made of clamshell (white) and slate (black).[39] The classic slate is nachiguro stone mined in Wakayama Prefecture and the clamshell from the Hamaguri clam; however, due to a scarcity in the Japanese supply of this clam, the stones are most often made of shells harvested from Mexico.[39] Historically, the most prized stones were made of jade, often given to the reigning emperor as a gift.[39]

In China, the game is traditionally played with single-convex stones[39] made of a composite called Yunzi. The material comes from Yunnan Province and is made by sintering a proprietary and trade-secret mixture of mineral compounds. This process dates to the Tang Dynasty and, after the knowledge was lost in the 1920s during the Chinese Civil War, was rediscovered in the 1960s by the now state-run Yunzi company. The material is prized for its colors, its pleasing sound as compared to glass or to synthetics such as melamine, and its lower cost as opposed to other materials such as slate/shell. The term "yunzi" can also refer to a single-convex stone made of any material; however, most English-language Go suppliers will specify Yunzi as a material and single-convex as a shape to avoid confusion, as stones made of Yunzi are also available in double-convex while synthetic stones can be either shape.

Traditional stones are made so that black stones are slightly larger in diameter than white; this is to compensate for the optical illusion created by contrasting colors that would make equal-sized white stones appear larger on the board than black stones.

Bowls

The bowls for the stones are shaped like a flattened sphere with a level underside.[40] The lid is loose fitting and upturned before play to receive stones captured during the game. Chinese bowls are again slightly larger, and a little more rounded, a style known as Go Seigen; Japanese Kitani bowls tend to have a shape closer to that of the bowl of a snifter glass, such as for brandy. The bowls are usually made of turned wood. Rosewood is the traditional material for Japanese bowls, but is very expensive; wood from the Chinese jujube date tree, which has a lighter color (it is often stained) and slightly more visible grain pattern, is a common substitute for rosewood, and traditional for Go Seigen-style bowls. Other traditional Chinese bowls include lacquered wood bowls, or woven straw or rattan baskets. Stone bowls also are traditionally used. The names of the bowl shapes, Go Seigen and Kitani, pay homage to two 20th-century professional Go players by the same names, of Chinese and Japanese nationality, respectively, who are referred to as the "Fathers of modern Go".[41]

Modern and low-cost alternatives

In clubs and at tournaments, where large numbers of sets must be purchased and maintained by one organization, expensive traditional sets are not usually used. For these situations, table boards are usually used instead of floor boards, and are either made of a lower-cost wood such as spruce or bamboo, or are flexible mats made of vinyl that can be rolled up. In such cases, the stones are usually made of glass, plastic or resin (such as melamine or Bakelite) rather than slate and shell. Bowls are often made of plastic.

Common "novice" Go sets are all-inclusive kits made of particle board or plywood, with plastic or glass stones, that either fold up to enclose the stone containers or have pull-out drawers to keep stones. In relative terms, these sets are inexpensive, costing US$20

Playing technique and etiquetteThe traditional way to place a Go stone is to first take one from the bowl, gripping it between the index and middle fingers, with the middle finger on top, and then placing it directly on the desired intersection.[42] It is considered respectful of the opponent to place the first stone to the player's upper right-hand corner. Although it can be soothing and pleasant to run one's hand through the bowl or hold a handful of stones, this can be noisy and unnerving to one's opponent; it is considered good form to take only one stone at a time as one decides where to play. It is permissible to strike the board firmly to produce a sharp click. Many consider the acoustic properties of the board to be quite important.[37] The traditional goban usually has its underside carved with a pyramid called a heso recessed into the board. Tradition holds that this is to give a better resonance to the stone's click, but the more conventional explanation is it allows the board to expand and contract without splitting the wood.[37] In theory, the wood never fully dries, so fully sealing it threatens warping in varying conditions. The heso allows the board to breathe.

Time control

See also: Time control and Byoyomi

A game of Go may be timed using a game clock. Formal time controls were introduced into the professional game during the 1920s and were controversial.[43] Adjournments and sealed moves began to be regulated in the 1930s. Go tournaments use a number of different time control systems. All common systems envisage a single main period of time for each player for the game, but they vary on the protocols for continuation (in overtime) after a player has finished that time allowance.[nb 5] The most widely used time control system is the so called byoyomi[nb 6] system. The top professional Go matches have timekeepers so that the players do not have to press their own clocks.

Two widely used variants of the byoyomi system are:[44]

Standard byoyomi: After the main time is depleted, a player has a certain number of time periods (typically around thirty seconds). After each move, the number of full time periods that the player took (possibly zero) is subtracted. For example, if a player has three thirty-second time periods and takes thirty or more (but less than sixty) seconds to make a move, they lose one time period. With 60–89 seconds, they lose two time periods, and so on. If, however, they take less than thirty seconds, the timer simply resets without subtracting any periods. Using up the last period means that the player has lost on time.

Canadian byoyomi: After using all of their main time, a player must make a certain number of moves within a certain period of time, such as twenty moves within five minutes.[44][nb 7] If the time period expires without the required number of stones having been played, then the player has lost on time.[nb 8]

Notation and recording gamesGo games are recorded with a simple coordinate system. This is comparable to algebraic chess notation, except that Go stones do not move and thus require only one coordinate per turn. Coordinate systems include purely numerical ("4-4 point"), hybrid ("K3"), and purely alphabetical. The Smart Game Format uses alphabetical coordinates internally, but most editors represent the board with hybrid coordinates as this reduces confusion. The Japanese word kifu is sometimes used to refer to a game record.

crate by : positifadi-hikaru.blogspot.com